EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

The purpose of this report and reason for our interest in engaging in this study, was to further review what we had already investigated from our own Cultural Vitality Index Project; the seemingly disparate distribution of funds and lack of resources in the Latino art and cultural field in the state of California. Three significant factors were at the heart of our effort:

Our goal was to use available database information to track trends and identify opportunities and challenges. In the course of our study we encountered a number of unexpected challenges in utilizing the data to quantify the presence of Latino arts organizations in California, notable consistency and accuracy in the collated data and the overall lack of participation by Latino arts groups. We veered toward evaluating the California Cultural Data Project process itself to help understand, identify and provide a more qualitative profile of the Latino arts community.

The purpose of this report is to begin to quantify funding to California-based Latino arts organizations and assess how equitably funding and resources are allocated among the sector and throughout the state. We explored how well the California Cultural Data Project (CDP) is able to serve the Latino Arts Community in order to improve its overall impact and use.

Results from this report reveal the following:

2

The Latino Arts Network makes several recommendations to help not only the CDP, but also the funders requiring CDP participation, get a deeper understanding of the challenges that California-based Latino arts organizations face in order to broaden participation:

This report is a first attempt to utilize the data as it relates to ethnically specific Latino organizations in California. In the course of our research we discovered that there were some issues and flaws in the process, and our report was not only to illuminate the funding community and general readership, but to also review the CDP in context of the study. While recognizing the value of the CDP, we have offered some observations not for criticism but improvement, and some recommendations not for minimization but to make it a more effective tool for the entire field.

We believe the vision of the California Arts Council, Cultural Data Project and Latino Arts Network are congruent when it comes to providing access and equitable representation to the greater arts and culture field in our state. We hope that the work done to date is a start but also has value to all parties and most importantly the arts organizations, communities and people we hope to serve by our effort.

Note: This interpretation of the data is the view of the Latino Arts Network and does not reflect the views of the Cultural Data Project.

3

INTRODUCTION:

The arts are not just a nice thing to have or to do if there is free time or if one can afford it. Rather, paintings and poetry, music and fashion, design and dialogue, they all define who we are as a people and provide an account of our history for the next generation.1

~ Michelle Obama

In 2012-13, the Latino Arts Network of California (LAN) conducted a study to explore the trends, challenges and impact of funding the arts and culture within the Latino community in California. In partnership with the California Arts Council and the California Cultural Data Project (CDP), LAN analyzed data as reported to the CDP through 2011, interviewed key stakeholders, and reviewed several other related studies to compile these preliminary findings.

As detailed in the article by Talia Gibas and Amanda Keil, “The Cultural Data Project and Its Impact on Arts Organizations” (March 2013)2 the CDP has been successful to date, but is looking at self evaluation to improve its lasting impact with both funders and arts groups. This report is an initial study which specifically addresses funding patterns in the Latino community, yet recognizes there is a need for further study and a deeper examination of the findings. These findings and conclusions reflect what can be surmised to date, as well as evaluate the impact of the CDP in the arts and culture field within the Latino community.

The Growing Population and Presence of Latinos in California ¡Aquí estamos y no nos vamos! (We are here, and we are here to stay!)3 ~ José Montoya, late poet, artist and co-founder of the RCAF

According to the Pew Research Center, Latinos are the nation’s largest minority group and account for more than half the overall population growth in the United States between 2000 and 2010.4 In 2013, Latinos numbered 53 million people in the country, representing 17 percent of the total population. Of the top ten diverse Hispanic origins, Mexicans are the largest segment and represent 65 percent of the overall Latino population.

The following data for this report are derived from the Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project’s “Mapping the Nation’s Latino Population: by State, County and City” 2013 report, as well as the 2012 American Community Survey, the 2010 U.S. Census, and U.S. Census Bureau county population datasets.

In California, Latinos comprise 40 percent of the population, making it the largest segment of any demographic groups living in the state. Estimates by demographers and social scientists vary, but it is projected that by no later than 2050, and possibly as early as 2025, the state will be 50 percent Latino. Also, the percentage of Latinos in the state will

4

continue to rise into a growing majority segment until leveling off over the coming 80-85 years.

Nationally and statewide, the Latino population is getting younger as the rest of the nation is getting older, with a median age a full 15 years younger than the majority population. Presently, the majority of the Latino population is well under the age of 21. By the year 2040, the United States will be a minority majority, and at higher levels of actual population, a larger number than previously seen in density, diversity and youth.

In 2012, Latinos in California averaged only half the annual income ($20,000) of the Anglo population ($40,000), ten thousand less than the African American population ($30,000). Fifty-two percent of the total Latino population is under 18 years of age. At least 30 percent of the under-18 population of Latinos lives at, or below the federal income and household poverty levels.

Even as immigration is now declining, California has led the way, with a full 40 percent rise in Latino population over the past thirty years, making it the home to the largest homogeneous and Latino population in the United States.

Although representative of every Latino country in the Western Hemisphere, the overwhelming percentage of the Latino population in California is of Mexican descent.

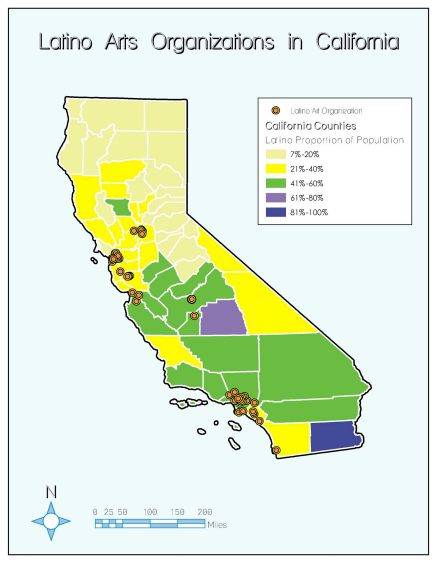

In California, 12 of the 58 statewide counties are majority Latino, including all major urban areas, notably Los Angeles County, (with nearly 5 million people, or close to 10 percent of the total Latino population). Five of the top ten largest Latino populations by county are in California. Also, 17 more counties have populations that are at least 25 percent Latino and 6 more counties are about to turn 25 percent Latino.

The distribution of the Latino population is statewide, with massive concentrations in the Southern part of the state and in the big cities. There are also very large Latino communities in all the agricultural regions, (notably Imperial County in the southernmost region of the state.) All 58 counties have a reported minimum Latino population of at least 7-8 percent, trending toward at least 10 percent in a very short time. (Exhibit A.)

Significantly only 15 of 58 counties overall in the CDP database are reported to have received funding. This equals only 26 percent of counties receiving funding for the arts. If we break this down further, since the 79 Latino organizations represent 5 percent of the total CDP database, we can extrapolate the breakdown of sparse demographic access even more dramatically when we recognize that 60 percent reflect zero funding in 2011 and those that were funded are located in only one quarter (1/4) of the entire state.

To restate, the Latino population represents 40 percent of the state, but in arts funding only about 2 percent, and in only one out of every four parts of the state.

5

What José Montoya affirmed in his “Aquí estamos…” statement is underscored by the dramatically shifting demographics of the largest state in the union. Latinos, mostly Mexicans, have been a significant part of the California population since the beginning, dating back to 1852 following the Mexican American War. As it has been the case with all the other states who border Mexico, a consistent stream of new immigrants have come to California since that time, particularly after the Mexican Revolution in 1910, and has only been tailing off in the past few years.

The Southwestern United States is indelibly Latino/Mexicano in the rooted culture and environment, for both Latino and non-Latino denizens, and has been an aesthetic influence upon artistic and cultural production despite a history of purposeful neglect or lack of recognition by the mainstream. Our state has not only been ground zero for the changing population trends; it will be the leader in forging a new composition of our national identity between now and the end of the century. The creation and presentation of Latino culture is vital to the future of the state for a variety of critical reasons.

The Value and Benefits of Arts & Culture:

La Cultura is la locura, y la locura is la cura. (Culture is the madness, and the madness is the cure.)5

This report operates with the premise, based upon a growing body of research over the past 25 years, that the Arts and Culture are vital assets and resources with great benefits and value for all Californians.

For the purpose of this study, with emphasis upon the Latino community, those benefits and values include:

6

Thus, Arts and Culture in California are not only essential to a healthy future but also vital toward preparing a prosperous and engaged population in the century to come.

METHODOLOGY:

Working with the California Cultural Data Project database, we first reviewed a data set of 1,746 California arts organizations. Composing an initial vetting, we culled the number of organizations down to 147 entries who identified themselves as Latino organizations, and finally, 79 ethnic-specific nonprofits who we identified as core Latino organizations. The basis of our selection of the 79 was by reviewing each group to determine if at least 50

percent board membership or staff was Latino, reviewing mission statements and by utilizing census information to confirm the geographic location of an organization in traditionally Latino communities. Several multicultural organizations were included in the 79 due to significant Latino programming and/or percentage of audience as reported.

It should be noted here that several important or well-known Latino organizations that are known to us through our own membership roster or through research, were not included in the core of 79 groups we studied, due to lack of CDP review-complete data or lack of participation in the CDP for reasons we cannot identify.

Additional methodology included:

7

FINDINGS:

The issue of equity and inclusion, which often gets left as the last thing you bring to the table, ought to be the first thing you bring to the table in order to engage the upcoming demographic.

~Dr. Manuel Pastor, Professor of Sociology and American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California

Arts Funding and Latinos in California:

The California Cultural Data Project details financial and other numerical data about 1,746 non-profit arts organizations in California of its members between the period 2006 and 2011. In our detailed analysis of arts organizations: 147 of these art organizations were self-identified Latino organizations and of that sub-group, only 79 were identified as ethnically-specific Latino organizations from our review.

In accordance with the information reported to the Cultural Data Report, the majority of Latino nonprofit organizations operate under $249,000 annually, with an annual average of $113,000 (2010).

To compare this to the macrocosm of nonprofits in California at large, we use the overall base figure of 11,000 arts and cultural nonprofits in the state measured by the Markusen Economic Research report “California’s Arts Ecology,” commissioned by The James Irvine Foundation.14 According to this study, California is home to 11,000 and by income breakdown: 4,950 of the nonprofits, or 48 percent earn less than $25,000 a year; 37

percent earn between $25,000 and $249,000 a year; 6 percent earn between $250,000 and $499,000 a year; 7 percent earn between $500,000 and $1.99 million a year. Overall, 85 percent of the almost 11,000 nonprofits in California, earn less than $249,000 a year.

In 2011, 44 percent of Latino organizations reported receiving zero income; or reported received no funding to the CDP. Those that do reflect income are found in only the most populous regions. Our assumption is that it is possible many of the organizations reporting did not correctly report income or were not able to report income in a timely manner, perhaps a reflection of vulnerability, staff availability or the economic downturn overall.

Nonetheless the figure is an indication of the capacity of the organizations to respond and utilize the CDP. Because the data is self reported and in the Latino arts organization subset, mostly un-audited, the figure underscores a flaw in the process to be addressed and reconciled.

8

In 2011, of those organizations reporting income, less than 35 percent of the total reported income was from traditional sources, including foundations, corporations and public or governmental sources. Approximately 15 percent came from foundations, 10 percent from the private sector and 10 percent from government (local/municipal, state, or federal) grants.

Again, some of the more well-known and larger Latino based arts organizations are notably missing from the roster of 79 we studied, and we were not able to use their data in calculating funding sources. This also indicates a concern with the CDP database regarding the completeness and inclusion of organizations in their membership.

Volunteers and In-kind Contributions:

Latino organizations reported a slightly higher level of volunteer participation in their organizations (15 percent). Data alone does not reflect the impact upon organizations, but we surmise that this number indicates a greater reliance on donated (in-kind) time and participation from at-large community members. In-kind contributions were also slightly higher than mainstream reporting, also indicating a higher level of impact from non-cash contributions upon Latino arts organizations.

Audiences and Programming:

A comparison of programming between Latino organizations and the mainstream arts field in California demonstrate a commensurate level of annual activity, including the number and frequency of public programs. However, working with far fewer financial resources, Latino arts organizations demonstrate an extraordinary efficacy at maintaining their activities and projects. (It was not possible to review the amount or cost of programming with the present database, and although we do not ascribe to the notion that the cost of programming is an indication of the quality of programming, it is a potential indicator of cost per event and percentage of annual programming that is part of the organizational budget and activities.)

Further, Latino arts organizations work with a smaller percentage of admissions and subscriptions revenue, given the limited capacity of their core audiences to invest in ticketing at the same level as mainstream audiences. At least 50 percent of the programming from the 79 core groups was free or low cost, fostering access as a priority over subscriptions, memberships and ticket sales.

Latino Youth and Virtual Media:

There is a substantial difference between Latino arts organizations and mainstream arts organizations regarding reporting of their virtual audience. According to CDP data, the virtual audience numbers of children for non-Latino organizations were almost 13 times

9

greater than the virtual audience reporting by Latino arts organizations. This reflects the gap in access to technology and virtual programming that exists for the Latino community.

National studies confirm that Latinos, specifically children 5-18, lag 25 percent in access and use of Internet technology. The disparate gap in virtual audience also indicates the gap in capacity of Latino organizations to offer online arts services such as podcasts, webcasts, instant streaming and website media content downloads. As electronic/online venues are a changing trend, it is obvious that Latino youth audience members are not keeping up with virtual attendance, due to a lack of computer access in the home.15

However, according to a new analysis of three surveys by the Pew Research Center, “Latinos own smartphones go online from a mobile device and use social networking sites at similar—and sometimes higher—rates than do other groups of Americans.” According to this study, in 2012, “86 percent of Latinos said they owned a cellphone, up from 76

percent in 2009 and the gap in cellphone ownership between Latinos and other groups either diminished or disappeared.”16

According to another NEA study, mobile devices appear to narrow racial/ethnic gaps in arts engagement. “Whether listening to music, looking at a photo, or watching a dance or theater performance, all racial/ethnic groups show roughly the same rates of engagement via mobile devices.”17 This trend reflects an opportunity for further engaging Latino youth in interest-driven arts creation and activity through smart phones, mobile devices and tablets.

Latino Arts Venues:

Of the 79 organizations we studied, only four indicated that they owned their own space, and the majority rented, leased, shared space or operated in donated spaces. The majority of the organizations utilize the space for a wide range of needs, but within arts disciplines, most of them operate as a multi-disciplined organization, whether they identify themselves as a single or sole discipline group or not. That is, they host partners, present other arts disciplines, collaborate with sister organizations, or rent use of space to more than one discipline. The majority of organizations also operate within their space with shared uses for educational, social or community services, non-arts related.

The Nonprofit Models of Operation in the Latino Arts:

Latino Arts Network was founded by a statewide network of arts organizations in traditional Latino communities, each with a range of 25 to 45 years of service, established during the apex of the Chicano art movement in California in the early 1970’s. They have been the backbone of a cultural connection between communities and artists, surviving transition of leadership and shifting demographics, growing audiences, and in some cases,

suffering, gentrification in their communities. In most cases, these cultural centers or ‘centros’ endeavor to serve newer and more generations without a commensurate growth in funding resources.

10

The majority of these ‘grandfather’ centros were established out of a necessity and a cultural mandate, given the creative and political explosion throughout the California Chicano communities of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. They have been the hubs of activity in the Latino Arts Network and remain vital to their respective communities.

Their most profound role today is to serve as proof that when there is such a center, a nexus or gathering place, there is greater cultural arts activity generated by the surrounding community. Thus the preservation of their role in the future of California is essential and warrants additional study and strategy to address the specific needs of these community-based cultural centers as a network connecting the cultural values of the entire state like a modern day version of the old El Camino Real.

Centros have also become the template for the standard contemporary Latino arts and cultural organization in California. For many of them, in order to survive (but also in line with a cultural aesthetic that comes from a non-Eurocentric point of view), they have become the new ‘peña,’ multi-user, multi-purpose, collectivized in operation, multidisciplinary and in collaboration with community interests that range from social services and youth organizations, to public partners and entities delivering family services, counseling, and in some cases, educational programming. The destinations or centers are arts meccas, but they often fortify their operations with the resources from non-arts delivery partners.

These organizations are cultural ‘farmers markets,’ one location addressing many needs. Their structure is like a tree with many roots and even more branches, which is how the arts are in context within the Latino aesthetic, a part of the overall culture and not apart from it. Thus their model is both a pragmatic invention and cultural design, reflective of cultural values and emerging of necessity. And in the Latino communities in California, their practical cross sector profile enhances their value as arts and cultural resources, a variation from the mainstream ideal of arts organizations, and difficult to capture using only quantitative data.

It has also been our experience and the result of our research through the LAN Cultural Vitality Index and other sources that there is a thriving presence of informal venues of arts and cultural production operating within the Latino community. In most cases, the informal groups (non 501c3), either created as a private entity by a small collective, or an interest-based arts group (such as a community-based ballet folklórico), is oriented toward preserving cultural legacy and practices from various Latin American mother countries. They are important grass roots cultural vessels, particularly in Latino communities with a large immigrant base. In most of these models, Spanish is the primary language.18

The formal, or established 501c3 arts organizations, such as those identified as the core 79 members represented in our study, are more aligned with traditional arts organizations profiles, usually chartered nonprofit models and operating in English as the primary language.

11

It should be noted that in either model, Spanish and English are not superior to one or the other, but merely the practical language as reflected in the core membership. In both profiles, Spanish and English are both necessary languages.

We have also learned that there is a growing number of newer organizations modeled in the standard nonprofit profile but are led by Latino entrepreneurs and self-starters, coming from a new generation of artists and practitioners. These organizations are straddling a line between nonprofit and for-profit, acting as small businesses but with community service or nonprofit mission, a hybrid model of operation.

EVALUATION:

We have not required applicants to our programs to complete the 11-section online form requiring annual updating because we feel it creates a barrier to accessing the grants process, especially for the small and mid-sized organizations we serve. In a state where over 44% of the state’s population speaks a language other than English at home, and the digital divide is still an issue according to income and education levels, we offer alternatives to foster greater access to our grants programs. 19

~Amy Kitchener, Executive Director, Alliance for California Traditional Arts

Reviewing the California Cultural Data Project:

The essential value of the California Cultural Data Project (CDP) is to provide a singular source of financial reporting that can be accessed by a range of users and for several applications or uses, in particular, reporting income and activity to a pool of funders within the philanthropic community.

Orientation and Preparation:

Ideally the preparation of one comprehensive report is easier than repeating and reformatting financial information for organizations with each funding request, and the data reports can be used by the organization itself for tracking finances and income, assessing its audience, and documenting its activities and programs. Our survey indicates that at present, the CDP fulfills much of its intent and goals, but that preparing the CDP

profile is still a greater burden in particular to smaller groups and organizations who do not have commensurate staff time and support as do the larger organizations.

Our research and feedback indicate that the amount of time required to fill out the CDP that is often predicted by funding agencies and representatives is far below actual practice, and that the amount of time to prepare and understand how to complete the CDP in order to utilize its many benefits was often cited to us as obstacles, especially with smaller organizations. Our conclusion is that the number of hours to complete the forms is underestimated, and the number of hours to maintain, update and amplify each of the CDP

12

years is also well under-estimated for the entire field and especially for small groups. In turn, the capacity or even desire to use the CDP as a resource diminishes if the value of the tool is seen as an obstacle rather than a benefit.

Terminology, Definitions and interpretations:

Use of templates can present unintended consequences. Although useful for simplifying massive data, template data is sometimes rendered inaccurate by a lack of understanding or how to apply the interpretation of terminology. As cited in their guiding principles for “Culture Counts in Communities: A Framework for Measurement” (Maria-Rosario Jackson, et al., 2002):

“Definitions depend on the values and realities of the community. Participation spans a wide range of actions, disciplines, and levels of expertise. Creative expression is infused with multiple meanings and purposes. And, opportunities for participation rely on arts specifics and other resources.”20

Our interviews with representatives in the field repeatedly referenced a need for clarification of terminology that is cited in the CDP. The most frequent concern was not some confusion in understanding the “art speak,” but how to interpret the meaning or intent of data field selections utilized to provide descriptions.

It says ‘arts service organization,’ so I figured, we do art and we serve the people with our music instruction, so we are an arts service organization, not just a mariachi.

~Comment from a field interview, identity with held by request

Consistency of language and terms, and how terminology is interpreted and valued reveal a need for further review and analysis of the language and meaning or value of categories and definitions used by the CDP and other tools that measure only financial and other numeric data.

The CDP does not fit the Latino experience. It’s simply not possible to do a one-size-fits all in today’s world. The fact that Latino art organizations are not participating in CDP should be a wake-up call to funders. 21

~Marie Acosta, Executive Director of La Raza Galería Posada in Sacramento

The challenge of “one size fits all” templates must be tempered with a clearer understanding from both the CDP and the user, to determine the intent and meaning of the terminology, size and scope of organizations, cultural sensitivity as well as the possible variations of each.

13

Alignment of Financial Information:

I sat down with my accountant and we looked over the CDP. After ten minutes he was cussing and saying to me, ‘One more damn thing to do!’

~Comment from a field interview, name withheld by request.

The CDP is designed to parallel a standard audit format and make the transfer of financial information easy to report. However, the audited financial statement is not a required aspect of the CDP, and for smaller groups, would represent yet another major challenge in fulfilling the obligation of the small organization. Because most small groups do not have audits, they are challenged to create CDP data, based on budgets or internal information at hand, such as a profit and loss statement, and the format is often a variation of data. This leads to painstakingly having to align how information is identified, noted or reported from one source to another.

Even with using a fully completed IRS Form 990, the same information is reported as required in one format but needs to be translated to another. The organization is further required to maintain an alignment between the internal information that is self reported, the CDP format, a 990 form format and if possible an audited financial statement format. The burden on smaller organizations is such that they will often elect to forego completing the CDP profile.

Additionally, most of the funder organizations requesting the CDP still ask for project budget, organizational budget and audits or balance sheets in addition to the CDP, thus compounding the requested data rather than making it easier or more streamlined for the applying arts organization.

We recommend a greater concentration on recruitment, orientation and help for these organizations so that they may become more fully engaged partners in the CDP, create a more positive profile of their operations, and enhance the capacity of arts organizations to solicit and procure funding from the philanthropic community.

For example, in the mid 1990’s, the Getty Foundation created a workshop series that were labeled “barn raisers” in which organizations were invited to attend and receive direct instruction on creating a website, at that time, a new tool to most arts groups. Utilizing the expertise of the presenters, the comfort and sanctuary of the collegial community, and prosaic instruction, the groups were able to construct the essence of their organization’s first website at the conclusion of the workshop. This kind of model of orientation could be useful for the CDP, as a supplement to the online orientation tools already in place.

14

You’re trying to deal with finishing your application, and then you have to get the CDP together? I can’t be the only one who has played with the numbers just to get rid of those red dots so I can get a draft to go through!

~Comment from the field, name withheld by request.

The County of Los Angeles Arts Commission is also exploring the possibility of including orientation to the CDP as a benefit of receiving a grant at the entry or small grant level, rather than making the CDP as a pre requisite of the application process. As cited earlier, the Alliance for California Traditional Arts has chosen to forgo the requirement of the CDP as a stipulation of its regranting application in order to facilitate access to grantmaking opportunities for its core community, also indicating a need for reconsidering how to engage more groups in the initial process and increase their enrollment in participating the CDP as a vital tool to gain greater access to funds.

Evaluating Audiences and Volunteers:

I reported subscriptions to our newsletter, which is free with membership, and then they called and asked me for a corresponding dollar amount. FREE is the dollar amount, FREE subscriptions with membership, and it is not earned income!

~Comment from the field, name withheld by request.

The present format for evaluating audience includes a detailed box office and subscription templates that is heavily directed toward performing arts organizations with sophisticated ticketing and season series packages. Even within the mainstream this is highly specialized data that only large performing arts groups are capable of tracking and reporting. There is no commensurate structure to evaluate participation from the audience at a small organization level, and the implication of the present form is that one is valued over the other, whereas the reality is that audiences are measured and counted differently depending on the size of the organization and the discipline or type of programming activity.

Connecting audiences to box office, sales and income is one effective measure, but only one and not the complete picture if left to it alone.

Volunteers are counted on the CDP by condensing the raw number of volunteers into full time equivalents. But that very practice minimizes the important number of total community stakeholders, particularly in small organizations, and particularly within the Latino community.

15

The number of volunteers for the event, who not only brought the food but then cooked and sold it for the feria was 30 mothers and some of the fathers, NOT 15 full-time staff equivalents, but 30 PEOPLE who came to help us. THAT is the important number! That’s 30 people who chose to join us, VOLUNTEER and help, not staff hours but donated time and community spirit. The numbers don’t tell the whole story.

~Comment from the field, name withheld by request

Special Note:

The majority of our interviews with arts organizations in the field resulted in three overriding themes:

The criticism ranged from strident outrage to clear and thoughtful analysis of the effectiveness of the CDP. But most of the commentary was critical, recognizing that the concept of the CDP is good, but not effective for them in its present state.

The majority of interviews with representatives in the funding community reflected a very positive endorsement of the CDP, citing the practical impact upon their granting process, particularly in tandem with a transition to online grant applications systems. One notable exception cited the lack of usefulness for their constituency, mostly small and ethnically specific or traditional arts practice groups. They chose not to require the CDP for applicants, citing their own research and discovering that it was keeping organizations from asking for funds rather than encouraging grant seeking for the groups in their field of service. Within the sum of the narrative of the funders we spoke with, several still recognized that the CDP was more likely to be useful to larger groups who have greater resources to facilitate the use of the data collection.

It should be noted that a number of sources of commentary were very willing to discuss their opinion of the CDP but only upon agreement that their name be withheld. The concern for the anonymity of the speaker was not a fear of reprisal from funders who may read this report; no one believes the field operates in that manner, but because they did not want to be seen as ungrateful to the effort from the philanthropic community to sustain their support of the arts and culture in California and in the Latino community.

CONCLUSION:

Data does not tell the whole story. In a best-case scenario, the accumulation of data is a worthy resource to measure activity and scope of activity, including impact and trends. But given some of the anomalies detailed in the report, and recognizing that the challenge of uniforming information into a single template that is inclusive of such a range of

16

diverse organizations, it is a daunting task. If in the end the goal of the CDP is to provide the big picture of the field, it needs to add color to the sketch, and strive to enhance its process to measure more than numbers.

It has been the challenge in the arts field since the onset of how to measure quantity and quality, but the very reason that has been a constant goal is because it is how we can best assess the impact of the arts upon society. Certainly within the creative field there are the resources and innovation, the creativity and the ambition to continue to explore a process and measure by which this can be achieved. The CDP is a good start, a good idea that needs to evolve into a better platform that will then be useful and valuable to both the funding community and the larger field.

In its present state the CDP is not useful to small organizations, of which the majority of Latino organizations are represented. It does not fulfill a primary objective that is important to those organizations, to facilitate greater and equitable access to resources and funding. The danger in not having complete information or participation is that the funders are not getting an accurate report of the field. The number of organizations, particularly among the smaller groups and groups representing communities of color in the state, are being undercounted and overlooked if they are not able to sustain their presence in the CDP, not the intent of the process, but an outcome that has become an issue.

The CDP is a good tool, and can be a valuable tool for the Latino arts and cultural community in procuring funds, measuring the remarkable vitality of activity of arts in Latino neighborhoods and communities throughout the state. But there are challenges to address to make the engagement a more accurate and meaningful partnership in the years to come.

This report is an initial effort to facilitate that process and recognizing the parameters and limits of the data and resources to study. It is a good start. We feel further study and more data is needed to delve deeper into questions regarding the per capita spending on youth in the Latino community, and using cross references such as data from the philanthropic community to get a more concrete indication of how much investment is in the Latino arts community in California.

Some nagging questions remain and require immediate attention. Given the current data, 40% of the population is getting 2% of the arts funding available in the state. If this figure is accurate, it is alarming and distressful. But working with unscientific data neither supports nor underscores the urgency of that condition. Can it be that of the almost 11,000 nonprofits in the state only 79 – and by that a generous roster of inclusion – serve Latino arts and culture? These are questions, which may not be answered now, but are worthy for future study as we head into the rest of the century and the future.

Note: This interpretation of the data is the view of the Latino Arts Network and does not reflect the views of the Cultural Data Project.

17

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Tomas J. Benitez is Chairman of the Board of the Latino Arts Network. He has been an advocate of Chicano/Latino arts and culture for 35 years, and has served as a consultant to the Smithsonian Institute, the President’s Council for the Arts, The National Endowment for the Arts, the University of Notre Dame, USC, UCLA, the Mexican Fine Art Center Museum in Chicago, and the California Arts Council.

Dr. Deborah DeVries has an extensive record in evaluating arts programs, education and research. She is co-founder of the Café on A / Acuña Gallery and Cultural Center and serves on the Oxnard Arts in Public Places Commission. She is a graduate of UCLA with a BA in History and Humanities, and holds a Master’s degree and Doctorate from USC in Education Evaluation of Programming. She has taught and served as a consultant for Chapman College of the Seven Seas, Golden Gate University, Park College, Embry Riddle University and UCSB.

Rebecca Nevarez is the Executive Director of the Latino Arts Network. She is dedicated to promoting the work of artists and advocating for Latino Arts in California and brings over 15 years of experience in nonprofit management to the field. She has held development positions at several arts institutions including Plaza de la Raza Cultural Center, California Institute for the Arts, the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Latino Theatre Company. Rebecca is a graduate of UCLA with a BA in History and Art History,

and her graduate studies included Public Art Studies at USC.

Very Special Thanks ~ Muchisimas Gracias!

Heather Bryant

Val Echavarria

Lora Gordon

Karina Macias

The California Cultural Data Project (CDP) is a unique system that enables arts and cultural organizations to enter financial, programmatic and operational data into a standardized online form. Organizations can then use the CDP to produce a variety of internal reports as well as those to be included as part of the application processes to participating grantmakers. To see a sample of the electronic data profile with a full list of the data collected there, please visit the California Cultural Data Project’s website: http://www.caculturaldata.org/content/CDP_blank_profile_2011.pdf

For more information on the Cultural Data Project visit www.culturaldata.org

Latino Arts Network of California (LAN) was founded in 1997 to serve as a voice for underserved Latino communities, and to advocate for greater awareness, inclusion, participation, funding support and promotion of Latino Arts and Culture as an important contribution to the national art landscape. The mission of LAN is to support and

18

strengthen the presence and production of Latino arts and culture in California and to advocate for the vitality of the artists and communities we serve.

For more information on the Latino Arts Network visit www.latinoarts.net

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This report was supported through collaboration between the California Arts Council and the California Cultural Data Project Working Group.

This interpretation of the data is the view of the Latino Arts Network and does not reflect the views of the Cultural Data Project.

Latino Arts Network of California

1443 E. Washington Blvd., #224

Pasadena, CA 91104 – 626/692-6560

Copyright c 2013 Latino Arts Network. All rights reserved.

Cover design by Val Echavarria

19

Exhibit A.

20

Endnotes:

Available at http://createquity.com/2013/03/the-cultural-data-project-and-its-impact-on arts-organizations.html

Montoya was one of the elders of Chicano art and literature and co-founder of the seminal RCAF artist collective, (initially called Rebel Chicano Art Front, later the Royal Chicano Art Front and today referred to as the Royal Chicano Air Force) in Sacramento, California.

http://www.nclr.org/images/uploads/pages/Implementation_Guide.pdf

21

http://new.livestream.com/artsusa/2013annualconvention/videos/21499984 14. (Markusen et al., 2011)

http://latinoarts.net/?page_id=61

Available at http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/310834_culture_counts.pdf 21. Marie Acosta, Latino Arts Network CVI interview and survey comments, 2013.

22

REFERENCES:

Acosta, Marie and Jeff Jones, “The City of Sacramento: A Case Study in Municipal Support of the Arts,” prepared for Latino Arts Network of California, 2013.

Aguilar, Orson, Tomasa Duenas, Brenda Flores, Lupe Godinez, Hilary Joy and Isabel Zavala, “Fairness in Philanthropy, Part I Foundation Giving to Minority-led Nonprofits,” The Greenlining Institute, November 2005. Available at

http://stage.greenlining.org/publications/pdf/339

Aguilar, Orson, Tomasa Duenas, Brenda Flores, Lupe Godinez, Hilary Joy and Isabel Zavala, “Fairness in Philanthropy, Part II Fairness from the Field,” November 2005. Available at http://stage.greenlining.org/publications/pdf/338

Americans for the Arts, “Art and Economic Prosperity IV,” 2012.

Available at

http://www.artsusa.org/information_services/research/services/economic_impact/iv/nation al.asp

Americans for the Arts, “National Arts Index,” 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012. Available at http://www.census.gov/acs/www/

Bronson, P.O., and Ashley Merryman, “The Creativity Crisis Newsweek,” 2010.

Brown, Anna and Mark Hugo Lopez, “Mapping the Nation’s Latino Population: by State, County and City,” The Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project, 2013. Available at http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/08/29/mapping-the-latino-population-by state-county-and-city

California Department of Education, “Common Core State Standards,” accessed September, 2013. Available at http://www.cde.ca.gov/re/cc/

Catteral, James, Susan A Dumais and Gillian Hampden-Thompson, “The Arts and Achievement in At-Risk Youth/ Findings from Longitudinal Studies,” University of York, UK, National Endowment for the Arts, 2012.

Foundation Center, “Foundation Funding for Hispanics/ Latinos in the United States and for Latin America,” Hispanics in Philanthropy, December 2011 and updated February 2012. Available at www.hiponline.org/resources/publications-and

recordings/resources/105

Gibas, Talia and Amanda Keil, “The Cultural Data Project and Its Impact on Arts Organizations,” < http://createquity.com> (March 2013). Available at http://createquity.com/2013/03/the-cultural-data-project-and-its-impact-on-arts organizations.html

23

Jackson, Maria-Rosario and Joaquin Herrenz “Culture Counts in Communities: A Framework for Measurement, The Urban Institute, 2002. Available at http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/310834_culture_counts.pdf

Jackson, Maria-Rosario, Florence Kawabasa Green and Joaguin Herranz, “Cultural Vitality in Communities,” The Urban Institute, 2006.

Jackson, Maria-Rosario, Florence Kawabasa Green and Joaquin Herrenz, Jr., “Art and Culture in Communities, Unpacking Participation, Policy Brief,” The Urban Institute, 2003.

Jackson, Maria-Rosario, Florence Kawabasa Green and Joaquin Herrenz, “Art and Culture in Communities: Systems of Support, Policy Brief,” The Urban Institute, 2003.

Kauh, Tina J., “After Zone: Outcomes for Youth Participating in Providence’s Citywide After School System,” The Wallace Foundation 2012.

Kitchener, Amy and Ann Markusen, “Working with Small Arts Organizations How and Why It Matters” Grantmakers in the Arts Reader, Vol. 23, No. 2, Summer 2012. Available at http://www.giarts.org/article/working-small-arts-organizations

Lopez, Mark Hugo, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera and Eileen Patten, “Closing the Digital Divide: Latinos and Technology Adoption,” The Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project, 2013. Available at http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/03/07/closing-the-digital-divide latinos-and-technology-adoption/

Los Angeles Stage Alliance, “Art Census Report,” 2011. Available at http://www.lastagealliance.com/pdf/2011LASTAGEArtsCensusReport.pdf

Lucero, Debra, “Art and Economics (Arts in Chico California),” Friends of the Arts, 2011.

Markusen, Ann, Anne Gadwa, Elisa Barbour and William Beyers, “California’s Arts Ecology,” The James Irvine Foundation, 2011. Available at http://irvine.org/news insights/publications/arts/arts-ecology-reports

National Center for Arts Educational Statistics, “Art Education in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools,” 2009-10.

National Council of La Raza, “Raising the Bar: Implement Common Core State Standards for Latino Student Success,” 2012.

National Endowment for the Arts, “How a Nation Engages with Art: Highlights from the 2012 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA),” 2013. Available at http://arts.gov/publications/highlights-from-2012-sppa#sthash.9NkaHWnV.dpuf

National Guild for Community School Education, “Engaging Adolescents: Building Youth Participation in the Arts” 2011.

24

National League of Cities Institute for Youth, Education and Families, “Strengthening Partnerships and Building Public Will For Out of School Time Programs,” Wallace Foundation 2012.

National Museum of Mexican Art, “Crescendo Cultural,” 2011. Available at http://nationalmuseumofmexicanart.org/exhibits/featured/crescendo-cultural

Peppler, Kylie, “New Opportunities for Learning in a Digital Age,” The Wallace Foundation, 2013. Available at http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/arts education/key-research/Pages/New-Opportunities-for-Interest-Driven-Arts-Learning-in-a Digital-Age.aspx

Ritter, Nancy M., Thomas R. Simon and Reshma R. Mahendra, “Changing Course: Preventing Gang Membership,” U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013. Available at http://nij.gov/topics/crime/gangs-organized/gangs/youth-gangs/welcome.htm

Southern Poverty Law Center, “Teaching Tolerance: Art and Activism,” <http://www.tolerance.org> (2013).

Stevenson, Lauren, Joe Landon and Danielle Brazell, “A Policy Pathway: Embracing Arts Education to Achieve Title I Goals,” California Alliance for Arts Education, 2013. Available at

http://www.artsed411.org/blog/2013/04/embracing_arts_education_achieve_title_1_goals

Taylor, Paul, Mark Hugo Lopez, Jessica Hamar Martinez and Gabriel Velasco, “When Labels Don’t Fit,” Pew Research Hispanic Trends, 2012. Available at http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/04/when-labels-dont-fit-hispanics-and-their-views of-identity/

U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey,” 2012.

Washington State Arts Commission, “Creative Vitality in Washington State,” 2010.

25

Latinos LEAD promotes more inclusive and effective civil society organizations by preparing and recruiting Latinos for nonprofit board leadership; helping nonprofit organizations to develop governing boards that reflect their constituents; and, collaborating with partners to increase ethnic diversity in nonprofit governance.